Bloating in anorexia recovery can be an unfortunate common side effect of eating more. It’s one of those things I wish I had a magic wand to make it go away. The first thing to know is that is normal, it often happens and it does pass if you keep going with eating enough. In this blog we go into what it is, why it happens and how you can help yourself, or a loved one, through this stage.

What is Bloating

“Bloating” can refer to symptoms such as wind, abdominal pain and an increase around the stomach area after eating. It can cause physical discomfort, making meals and daily life feel harder. For those struggling with body image, bloating can

Now bloating is common and is a natural part of digestion in all of us. Bloating doesn’t necessarily mean something is “wrong,” but understanding why it happens can help reduce fear and frustration, especially during recovery, you can read what the NHS has to say about bloating in general; however, let’s dig into the specifics of bloating in anorexia recovery.

Bloating in anorexia recovery: changes in the body

When food is severely restricted, the body doesn’t recognise this as a choice; it interprets it as famine. To survive, it slows down many functions to conserve energy and resources.

Bloating in anorexia recovery is to be expected. Even when you start eating again, your gut, hormones, and nervous system need time to trust that food is coming regularly again. These symptoms are usually a delayed effect of the illness, not something you’re “doing wrong.”

- Your gut is still adjusting, so eating more can feel uncomfortable.

- You often have to eat even when you feel “full,” which can increase pressure and distension.

- Stress and anxiety can heighten digestive symptoms.

- Hormone fluctuations can affect digestion and water balance, leading to bloating on some days more than others.

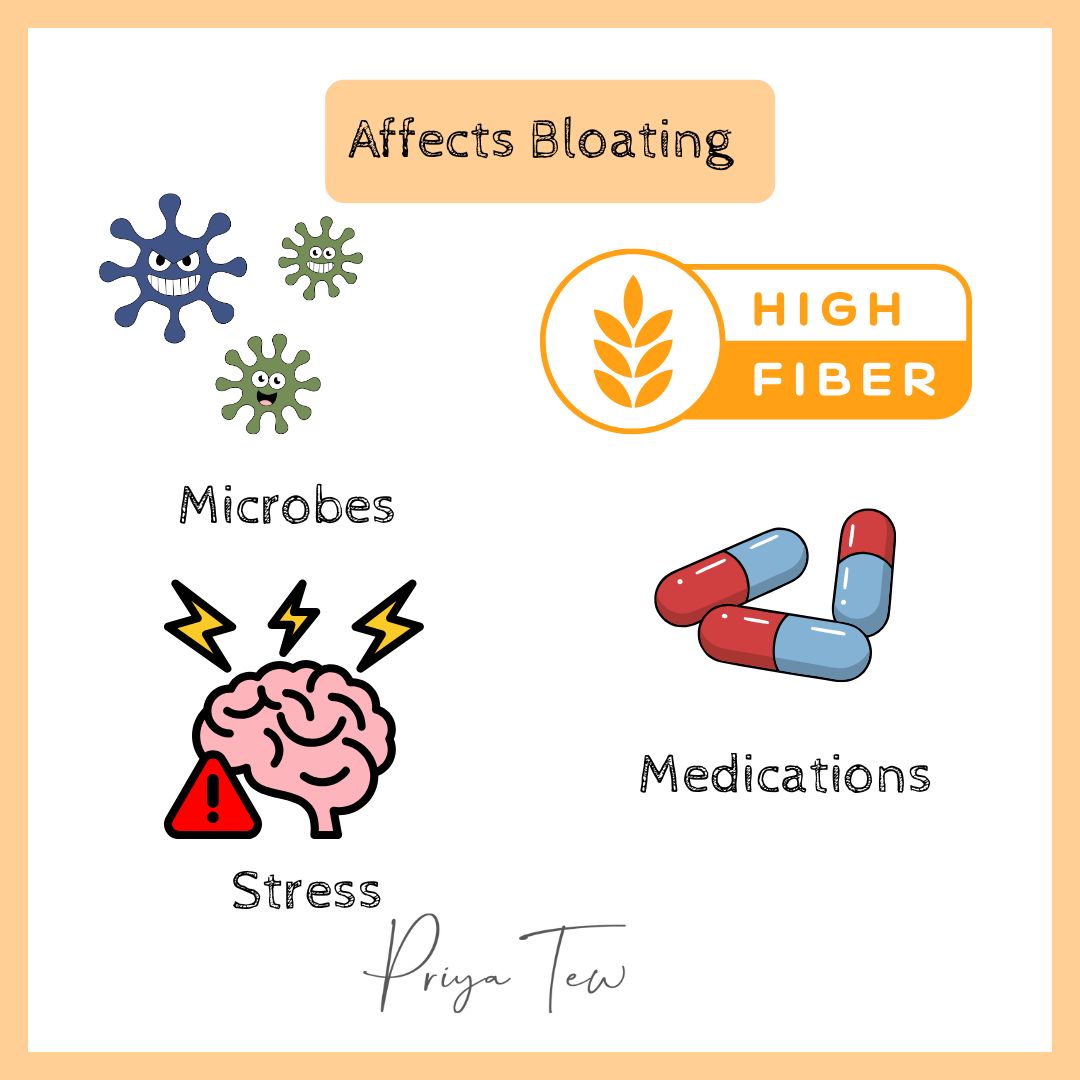

- More fibre in your diet can temporarily increase fermentation and gas.

- Water retention can make bloating more noticeable day to day.

- Some medications may add to bloating, though they play an important role in recovery.

The good news: with time, consistency, and gentle patience, your body usually regulates itself again. These symptoms are temporary, even if they feel intense in the moment.

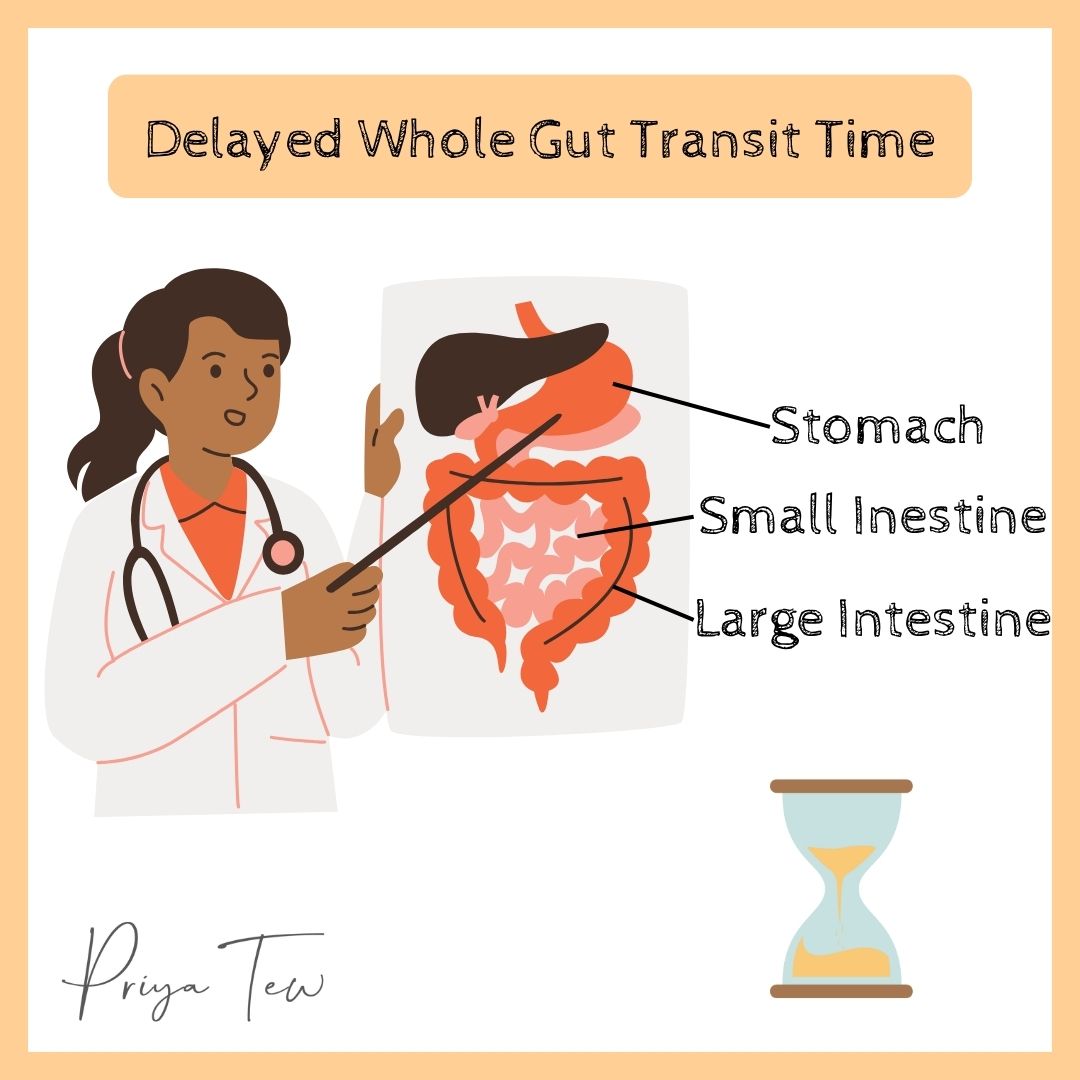

Delayed whole gut transit and gastroparesis

When the body has been undernourished for a long time, the muscles and nerves that control digestion slow down and do not work as well as they should. This makes it harder for food to move through the gut efficiently. The stomach and intestines are muscles, if you lose muscle mass they can be affected plus with less food passing through they do less muscle training work and can weaken. Let’s go into more detail:

Gastroparesis occurs when the stomach empties food more slowly than normal, even though there’s no physical blockage. This can cause bloating, early fullness, nausea, burping, and discomfort after eating.

But the effects don’t stop at the stomach. Undernutrition can weaken the entire digestive tract, leading to delayed whole gut transit, where food moves more slowly from start to finish. This can also include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), often made worse by reduced saliva production, which can make swallowing feel dry and uncomfortable.

As food moves down the digestive system, its passage through the small and large intestines is delayed. Food and waste linger longer than ideal, causing bloating and gas build-up. In the colon, the longer the stool sits, the more water gets drawn out, often leading to constipation.

Microbial imbalance

The gut microbiome plays a huge role in overall health. Gut microbes digest and ferment foods (our high fibre foods) that we otherwise couldn’t break down. As a by product the microbes produce short chain fatty acids and other beneficial products that support our digestive health, immunity, and so much more!

However, these microbes are sensitive to changes in diet. Each species tends to thrive under specific conditions, and if their preferred “food” is cut out or drastically reduced, they can struggle to survive. That means if you restrict your diet, you can impact your gut microbiome.

It’s been found that people with anorexia have different gut microbiome profiles. Certain types of helpful bacteria can be reduced, while other less helpful ones may increase, creating an imbalance. These shifts can affect how food is digested and fermented, which can contribute to bloating, gas, constipation, that we spoke about earlier, but also changes in mood.

High fibre diets

Some people with anorexia can fill up on high-fibre foods like fruits and vegetables. Whilst this may seem a good thing as fibre is important for gut health, too much is not helpful. When your digestive system is struggling, too much fibre can worsen bloating, gas, and lead to tummy pain. The gut can struggle to move food along at its usual pace, giving microbes more time to ferment fibre and produce gas.

Medications and substances

Things like caffeine, laxatives, and certain sweeteners can irritate or slow the gut further, which may worsen bloating and discomfort. In addition, some antidepressants, often prescribed to support mental health during anorexia recovery, can also affect normal digestive function. These medications may contribute to bloating, gas, or changes in bowel habits. While this can feel frustrating, they play an important role in recovery and should only be adjusted under medical guidance.

Stress

Mental health factors like stress, anxiety and low mood can make these symptoms worse (because of the gut–brain connection), so both nutritional support and psychological support are important in recovery.

Tips for reducing Bloating in Anorexia Recovery

Whilst bloating can feel so uncomfortable and like it will go on forever, it will pass. Once regular nutrition is reintroduced, the whole gut tends to reregulate itself, often improving quite quickly, even before weight is fully restored. In other words, this is usually a reversible effect of the illness, not a permanent problem.

DO’s

Tip: During periods of discomfort or bloating you may find these tricks ease up some of that for you

- Stick to your eating plan. The routine is essential. Your digestive system needs to relearn how to digest and function properly. Regular eating gives it practice through the day and the timings help it know when to prepare to expect food. Skipping or restricting meals can make symptoms worse and prolong the bloating.

- Hot water bottle A hot water bottle or heat pack on your tummy can be so helpful. The warmth helps bring blood flow to the digestive organs, easing constipation, soothing discomfort, and providing a sense of calm.

- Peppermint. A warm cup of peppermint tea or even Fox’s Glacier Mints can help ease bloating and IBS-like symptoms. A study was done using these mints in anorexia and it really had a postive impact. Peppermint can help relax the muscles of the digestive tract, supporting easier movement of gas and food.

- Gentle movement. Relaxing and gentle movements, like soft yoga stretches, can encourage the gut to get moving again. A slow, clockwise abdominal massage (starting from the right side under the ribs, down toward the pubic bone, and following the path of the large intestine) can relieve gas and pressure.

- Breathing Exercises. Practising deep diaphramatic breathing can help calm the nervous system, ease tension in the abdomen, and support digestion. A few slow, deep breaths can make a real difference when bloating feels overwhelming.

- Loose clothing. Wearing loose, comfortable clothing that doesn’t put pressure on your abdomen can make bloating feel much less uncomfortable.

- Increase fibre intake slowly. Fibre is important for gut health, but after periods of undernourishment, introducing it too quickly can make bloating worse. Gradual increases give your gut microbes time to adapt and help reduce discomfort. Work with your dietitian on how to increase this to have less bloating symptoms.

- Fact-check the ED voice. Bloating can be triggering, but it’s not a sign of weight gain or failure. Remind yourself: this is a temporary and expected part of recovery. Challenge any unhelpful thoughts your eating disorder may feed you during this time.

DON’Ts

Cut out foods. There’s a growing trend around “anti-inflammatory,” low FODMAP and other exclusion diets. While these approaches can be helpful for some people, they usually require professional supervision to be done safely. During active recovery, cutting out foods is not recommended.

Unless you’ve been medically advised of a specific allergy or intolerance, removing foods to “relieve bloating” can actually make your gut more sensitive and increase fear around eating. In most cases, your body simply needs time to relearn how to digest a variety of foods again.

Take Home Message

Bloating in anorexia recovery is uncomfortable and can make you want to take a step back, but it’s also a normal and expected part of healing. It happens because your digestive system is relearning how to function after a period of undernourishment. With regular meals, hydration, patience, and support, your gut will begin to find its rhythm again. This is temporary! Your body is not broken; it’s healing.

You can work with Priya on this step by step. Take a look here.

Most importantly, remember: recovery doesn’t have to be perfect to be working

References

- Jafar W, Morgan J. Anorexia nervosa and the gastrointestinal tract. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul 1;13(4):316–24.

- Ruusunen A, Rocks T, Jacka F, Loughman A. The gut microbiome in anorexia nervosa: relevance for nutritional rehabilitation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2019;236(5):1545–58.

- Stanculete MF, Chiarioni G, Dumitrascu DL, Dumitrascu DI, Popa SL. Disorders of the brain-gut interaction and eating disorders. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun 28;27(24):3668–81.