Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea (FHA) is something that I come across alot in my clincial work and I don’t think it is talked about enough. If you have disordered eating, a restrictive eating disorder, if you exercise to a high level or have gone through a highly stressful period of time then this post could apply to you. If not it could be useful to read for a friend or family member, so please do read on. Huge thanks to Eimer McCoy her help on this post.

What is Amenorrhea?

Amenorrhoea is the medical term used to describe ‘no periods’ 1. There are two main types of amenorrhea: primary and secondary. Primary amenorrhea occurs when a woman never starts her period in the first place, which is usually due to genetic or anatomical reasons 1. Secondary amenorrhea on the other hand occurs if someone has had regular periods, but their periods stop completely for more than 3 months 2. Secondary amenorrhea can also be defined as having irregular periods for more than 6 months 2. It is normal for women to miss a period from time to time, it’s only when it is missed for several consecutive months that it may be amenorrhea.

Note: Amenorrhoea is different from oligomenorrhea, which is the medical term for ‘irregular periods’. Oligomenorrhoea occurs when the gaps between periods keep changing unpredictably 3.

Menstruation: The Basics

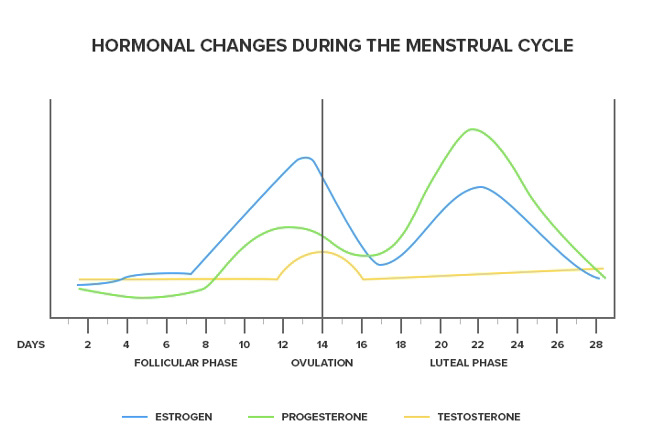

To help you fully understand FHA let’s take a brief look at the physiology behind menstruation.

Menstruation describes the female period. Each month women’s body’s prepare for them to become pregnant. A complex system of hormones released from the brain controls the menstrual cycle 4. Each month rising levels of the hormone oestrogen cause the ovary to develop and release an egg (ovulation) 4 . Alongside rising levels of oestrogen, progesterone levels also increase causing the endometrium lining of the uterus to become thicker and softer creating a perfect environment for an egg to implant 4. If an egg does not implant and isn’t fertilised, the thicker endometrium layer sheds and we get the bleeding we know as a period. The cycle then begins again and the process repeats itself each month. The average cycle length of a period is 28 days with 5 days of bleeding 4,5.

What is Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea (FHA) ?

FHA occurs when the hypothalamus slows or stops producing certain reproductive hormones 6. The hypothalamus is found at the base of the brain and plays an important role in releasing reproductive hormones. It produces a hormone known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH signals the production of other hormones needed for egg maturation and ovulation, such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) and oestrogen 5. Sometimes the hypothalamus does not produce sufficient amounts of GnRH which can in turn reduce the amount of other reproductive hormones (FHA, LH oestrogen) produced and lead to the cessation of ovulation and menstruation 5.

Causes

While reversible, the causes of FHA are mainly related to psychological stress, excessive exercise, disordered eating, low body weight or a combination of the above 7. When the body is put under severe stress, it stops menstruating. This is believed to be an evolutionary response in which the body prioritises supporting other ‘more important’ aspects of physiological health rather than menstruation 7. While anyone can experience FHA there are certain groups of women who are more at risk:

- Women with eating disorders or disordered eating: Some characteristics that contribute to FHA are common in women with eating disorders or disordered eating such as, calorie restriction, excessive exercise, and/or psychological stress 8.

- Professional athletes: Even women that are eating enough may experience FHA if they are athletes 9. This is because they are putting their body under high physical stress by intensely exercising. Many athletes lose their period by being in a slight, persistent energy deficit—oftentimes unknowingly. This is called Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome or REDs for short 9.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of FHA is a diagnosis of exclusion. This means that other conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia and polycystic ovary syndrome have to be ruled out before FHA can be diagnosed. The diagnostic process can therefore be a lengthy one 6.

Consequences of FHA

There are several long term consequences associated with FHA:

- Cardiovascular consequences: Research has linked hypoestrogenism (low levels of oestrogen) in young women to premature CVD 10. CVD refers to conditions that affect the heart and/or blood vessels. An early clinical sign of hypoestrogenism is menstrual cycle irregularities which is a feature of FHA. Research from the Nurses’ Health Study of over 82,000 women found that the more irregular the menstrual cycle in young women the greater the risk for future CVD events (up to a 50% increase) 11.

- Bone health: Oestrogen plays an important role in maintaining healthy bones as well as healthy menstrual cycles 12. Having low oestrogen levels can significantly affect women’s bone status as it impacts the absorption of calcium and can pose a risk to young women for developing osteopenia or osteoporosis at an early age and/or over their lifetime 12.

- Psychological impact: While psychological stress can contribute to the onset of FHA, this relationship can go two ways, in that FHA greatly impacts the psychological status of affected women. Women with FHA have been shown to have significantly higher depression scores and greater anxiety, compared to those without FHA 13. Perfectionistic behaviour and extra attention to the judgments of others has also been found to be more common in women with FHA in comparison to eumenorrheic counterparts13

- Fertility: Unfortunately, untreated, and prolonged FHA can impact reproductive health15. FHA typically occurs during peak reproductive years, resulting in anovulation (the lack or absence of the release of an egg) and infertility. Anovulation can prevent women from becoming spontaneously pregnant 14. Prolonged amenorrhea can make it more difficult to get pregnant and therefore, women often need to set aside time in their family planning schedule to regulate their menstrual cycle.

Treatment

The aim of FHA treatment is to re-establish a regular ovulatory menstrual cycle. The choice and success of treatment depends on the initial cause. A holistic approach to treatment that addresses the underlying cause of stress is often the most effective. This may include treatment for disordered eating, stress management and/or excessive exercise.

Treatment options:

- CBT : Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be a successful treatment option for FHA 16. It can help lower levels of stress through lowering cortisol levels (stress hormone) in women with FHA.

- Seeking advice from a registered dietitian : A dietitian can help you improve your energy balance and relationship with food. Advice may be centred around increasing calorie consumption, rebuilding your relationship with food and your body, improving nutritional quality of the diet and/or reducing physical activity levels.

- Stress management: Mediating stress through incorporating stress management practices has been shown to help treat FHA. Stress management techniques may include yoga, journaling, sleeping sufficiently and CBT.

- The pill : While this could sound like a good option, it’s contencious. Oral contraceptive therapy (or the pill) is an oestrogen replacement that provides a withdrawal bleed, however it is not intended to support the resumption of normal hormone activity. The underlying cause of FHA still needs to be addressed and this is something we would suggest you work on first. Therefore the endocrine society clinical practice guidelines suggest against women with FHA using oral contraceptive pills for the sole purpose of regaining menstruation 6.

Note: What treatment method works for one person may not work for another. That is why it is important to seek individual advice from a healthcare professional.

Conclusion:

FHA is reversible and can be managed with the right support. If you are concerned that you may have FHA please seek help from a registered healthcare professional such as your GP. Restoring your period can be a lengthy process but it is worth it and can bring long term healing to your relationship with food and your body.

Created by : Eimear Mc Coy (IG profile: @health_aligned)

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)., 2021. Amenorrhea [online]. NICE. [Viewed 07 July 2021]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/amenorrhoea/

2. MCCLINTOCK, A. & KAMINETZKY, C., 2020. Approach to Secondary Amenorrhea, in Chalk Talks in Internal Medicine [Online]. Springer International Publishing. pp. 295–299. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-34814-4_46

3. NHS., 2018. Irregular Periods [online]. NHS. [Viewed 5 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irregular-periods/.

4. JARRELL, J., 2018. The significance and evolution of menstruation. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology [online]. 50, pp. 18–26. [Viewed 3 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29530426/

5. MIHM, M., GANGOOLY, S & MUTTUKRISHNA, S., 2011. The normal menstrual cycle in women. Animal reproduction science [online]. 124 (3), pp. 229–236. [ Viewed 2 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378432010004148

6. GORDON, C. M., ACKERMAN, K. E ., BERGA, S. L., KAPLAN, J.R., MASTORAKOS, G., MISRA, M., MURAD, M H., SANTORO, N. F., WARREN, M. P., 2017. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism[online]. 102 (5), pp. 1413–1439. [Viewed 1 July 2021]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/102/5/1413/3077281

7. MECZEKALSKI, B., PODFIGURNA-STOPA, A., WARENIK-SZYMANKIEWICZ, A., GENAZZANI, A, RICCARDO., 2008. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: Current view on neuroendocrine aberrations. Gynecological Endocrinology [online]. 24 (1), pp. 4–11. [Viewed 2 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18224538/

8. KLEIN, D. A. & POTH, M. A., 2013. Amenorrhea: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. American Family Physician. 87 (11), PP. 781–788. [Viewed 3 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0601/p781.html

9. STELLINGWERFF, T., HEIKURA, I, A., MEEUSEN, R., BERMON, S., SEILER, S., MOUNTJOY, M.L., BURKE, L,M., 2021. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Medicine (Auckland) [online]. [Viewed 7 July 2021]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-021-01491-0

10. O’DONNELL, E., HARVEY, P,J ., GOODMAN, J, M ., DE SOUZA, M, JANE., 2007. Long-term Estrogen deficiency lowers regional blood flow, resting systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in exercising premenopausal women. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology And Metabolism [online]. 292 (5), pp. 1401–1409. [Viewed 1 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17227959/

11. SOLOMON, C. G., HU, F. B., DUNAIF, A., RICH-EDWARDS, J.E., STAMPFER, M.J., WILLETT, W.C ., SPEIZER, F. E ., MANSON, J,E.,2002. Menstrual Cycle Irregularity and Risk for Future Cardiovascular Disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism[online]. 87 (5), pp. 2013–2017. [Viewed 4 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11994334/12. MECZEKALSKI, B., PODFIGURNA-STOPA, A & GENAZZANI AR., 2010. Hypoestrogenism in young women and its influence on bone mass density. Gynaecological Endocrinology [online]. 26 (9), pp. 652–657. [Viewed 7 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09513590.2010.486452

. MARCUS, M. D., LOUCKS, T, L ., BERGA, S, L., 2001. Psychological correlates of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Fertility and sterility [online]. 76 (2), pp. 310–316. [Viewed 4 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11476778/

14. JUUL, A., HAGEN, CP., AKSGLAEDE, L., SØRENSEN, K., MOURITSEN, A., FREDERIKSEN , H., MAIN, KM., MOGENSEN, SS., PEDERSEN , AT., 2012. Endocrine evaluation of reproductive function in girls during infancy, childhood and adolescence. Endocr Dev[online]. 22, pp. 24–39. [Viewed 8 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22846519/

15. SHUFELT, C.L., TORBATI, T., DUTRA, E., 2017. Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and the Long-Term Health Consequences. Semin Reprod Med [online]. 35 (3), pp. 256-262 [ Viewed 1 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6374026/#R49

16. MICHOPOULOS, V., MANCINI, F., LOUCKS, T.L., BERGA, S.L., 2013. Neuroendocrine recovery initiated by cognitive behavioural therapy in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertility and sterility [online]. 99 (7), pp. 2084–2091.e1. [Viewed 5 July 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23507474/

Well done. Thank you